Left-to-right reading for [10:0]u8 could be ten-long zero-terminated array of u8s.

Also, it seems you meant to call the post “Intuitive Zig type pronunciation”.

I did mean unintuitive, but can see how it could be confusing. I’ve changed the title.

Pointers with custom alignment might be a little awkward to read left-to-right:

[]align(4) u8

Instead of “slice aligned-to-4-bytes of u8s”, I really wanna say “4-byte-aligned slice of u8s”.

you shouldn’t even if you want to, because it’s not the slice itself being aligned, it’s what it points to (or at least that’s how I interpret “slice aligned to”).

const foo : []const u8 align(1) = "arst";

const foo_pointer = &foo; // *align(1) const []const u8

this is how you define an aligned slice (i.e. alignment of the memory location where the slice “struct” is stored at)

to be fair the position where you put this information is not particularly intuitive from the perspective of pronouncing a type name

So, is this wrong then?

I believe so, and also N does not refer to the alignment of each T element, just of the first one, an aligned string won’t have padding between individual bytes if you think about it.

I get it now, I, as well as the post I linked to, meant the same thing by “N-byte aligned slice”. Meaning the alignment of the pointer that the slice struct stores.

I got used to conceptualizing slices as pointers to arrays since there’re often coercible.

@Calder-Ty There’s a typo in one of the sentences, “sentinal” instead of sentinel.

I agree that the type syntax is intuitive and easy for humans to parse. The left-to-right reading direction for type prefixes is also consistent with generics: []T and ArrayList(T) are both read as “slice/array list of T”.

However (slightly off-topic), when I first started writing Zig I found it unintuitive and confusing that arrays [n]T and slices []T both used square brackets, since one represents a value and the other a pointer/reference (a very important distinction, and from what I’ve seen this trips up a lot of beginners). What’s more is that slicing with a comptime-known endpoint yields *const [3:0]u8 and a runtime-known endpoint [:0]const u8, with const and the other attributes on different sides of the brackets. Which makes sense once you understand that * and [] are both pointers, but still feels a bit inconsistent at first until it eventually becomes second nature.

I think the array/slice syntax is fine and I wouldn’t want to change it, but if I were to design a language I would probably do something like this:

// 9-length 0-terminated array of T

[9:0]T

// pointer to 9-length 0-terminated array of T

*const [9:0]T

// pointer to unknown-length 0-terminated array of T

// (unknown-length arrays can't be instantiated/dereferenced, like opaques)

*const [:0]T

// "fat pointer" (slice) to unknown-length 0-terminated array of T

#const [:0]T

One way to think of it is [] means “indexable”.

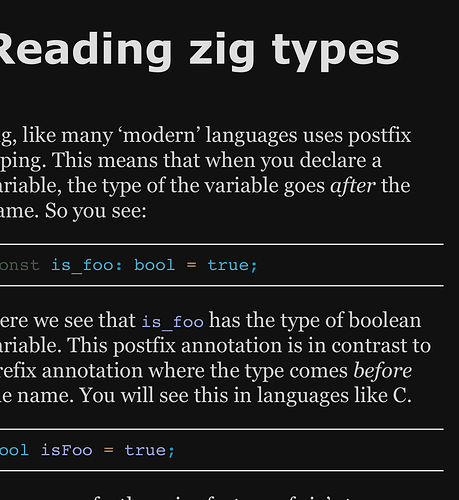

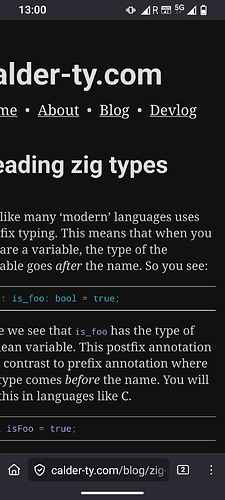

The CSS on your site appears to have a bug on mobile (iOS). The text does not fit within the screen and it is impossible to zoom to fit it.

It is fixed indeed, I’m glad I could help

Works now on Firefox iOS but not safari

Languages (human ones) always have irregular forms, I’m convinced there are deep reasons for this.

My take on sentinels is that it works the only way it can work: for one thing, the sentinel modifies the type. When defining an array, the number after [ is always the length of the array, it would be very strange indeed if the sentinel could push it out of the way, and that wouldn’t read strictly left to right either: if you saw [, 5, you’d have to change your mind about what you’re looking at if you see :, now 5 is the sentinel value and you have to “reset” and read the length.

For another thing, the sentinel goes at the end of the array, and we write literal array values from left to right. So the sentinel is specified where it goes, and this is cognate with how we slice to get a sentinel: arr[0..len :0].

We don’t actually read left-to-right either, information sometimes needs to propagate backward, classic example from linguistics is “time flies like an arrow, fruit flies like a banana”.

So I would go so far as to argue that the way Zig writes a sentinel does read from left to right, it’s just that we rearrange it slightly when translating it to English. I’d venture that for most fluent programmers, code is generally read as code, and not translated from Zig (which is a language) to English, or whatever native language one is most comfortable with. That mechanism exists, but it’s slow mode, it’s what we use when we aren’t sure what we’re looking at.

We can all read:

while (m_node) |node| : (m_node = node.next) { ... }

But it doesn’t cleanly translate to English, does it. “while m_node, node, m_node equal node dot next” is a Zig sentence, not an English one. I would not personally think the word “equal” in parsing that, either.

I think having one simple rule (read left to right) which gets you 90% of the way there, with a wrinkle or two where it makes sense, is basically ideal. Niklaus Wirth got this stuff right the first time, and I’m glad we got back to it.

I agree this is confusing, this and auto-dereference (there is no -> in Zig) favor experienced developers over beginners.

What makes it gel for me is actually [*]T, a bare pointer you’re allowed to index (but cannot dererence directly). A slice is really [*,len]T, a [*]T which carries its length with it. All of that gets elided because a slice is the common case, and multipointers are the uncommon case.

But I was looking up the exact syntax for this or that esoteric operation on array / slice / sentinel / multipointer declaration and conversion, long after I was basically done checking the docs for straightforward syntax stuff. I still do occasionally.

It’s a case where the syntactic complexity reflects the inherent complexity, and I can’t imagine improving on how Zig does (I’m quite imaginative).

This would be a good topic for the Docs section though.

I think you are correct here. In practice the sentinel terminated syntax rarely causes me issues, but starting out, it was foreign. In other words when i didn’t know what i was looking at. When we read natural language we read words as whole parts. That’s why we are able to decipher words, even when they are misspelled. I think the same thing happens here. It’s easy enough to see [10:0] as a whole unit, and once we have that down, the ordering really doesn’t trip you up. Indeed the ordering is natural, as you say, because the sentinel is where it belongs, at the end. I just find it an interesting exception to the general rule.

It make a good hook for a blog post, introducing the ‘regular’ rule in terms of an irregularity in the pattern. I liked it ![]()